Abstract:

Joe Zawinul’s 55-year musical career was marked by three major periods: his stint with Cannonball Adderley (1961–1970), the ensemble Weather Report (1970 – ca. 1986) and his own The Zawinul Syndicate (1988–2007). Thus considered, his stylistic development began with hard bop and soul, paving the way for his own debut jazz-rock recordings (1966), then continuing to more avant-garde, experimental forms with Miles Davis (1968–1970), and finally leading to a broader combination of jazz-rock and what came to be known as world music – and what Zawinul himself considered to be something other than jazz. This final chapter in Zawinul’s career, essentially congruent with the Zawinul Syndicate period, is the focus of this study. Zawinul’s musical style with the Syndicate – in particular his sound, harmony, conception of time, musical density and ballad playing – is first considered. Further, the issue of whether or not stylistic elements typical of the Syndicate era were present with Weather Report, or even earlier, is discussed. Hence, such elements can be traced back to his early career, emerging as characteristics not only of his work in the last two decades, but also of the musician in general.

Joe Zawinul’s life work as a musician encompasses three main periods:

– his time with Cannonball Adderley (1961–1970),

– the ensemble “Weather Report” (1970–1986), and

– the band “The Zawinul Syndicate” (1988–2007).

Zawinul realized his greatest success with Weather Report; together with Wayne Shorter, he was mainly responsible for the band’s repertoire and incisive style. The development leading to this style took place years before the band’s inception, finally resulting in Zawinul ending his – up to that point fruitful – collaboration with Cannonball Adderley:

“At the beginning, in the first years – and that took a very long time – I didn’t have my own style. I got my own style around 1965, 1966, not before – after years in America. Before that I was playing well, but playing bebop the whole time. I began to try, every time I was about to play a phrase that I had played before . . . [Interviewer:] . . . to play it differently? [Zawinul:] No, not just to play it differently. More radical: to play something different. But as soon as I noticed myself starting to develop something like my own style, it suddenly got difficult in Adderley’s band. At first I tried to write a lot more original pieces, where I could express myself better. But that was the beginning of the end. I felt more and more that I had reached my own limits. The first time I was really able to express myself was with my own band, with Weather Report.”1

Weather Report required several years of musical experimentation before finally, beginning with the 1973 album Sweetnighter, hitting upon the formula that – particularly from 1976 on – would resonate internationally with a broad audience.

After the disbanding of Weather Report in 1986, Zawinul began performing publicly in 1988 with the ensemble known as the Zawinul Syndicate. This band existed until his death in 2007; its music was often characterized in the media as “world music” – a designation that, in its dissociation from the mainstream jazz canon, was welcomed by Zawinul.2 Though primarily a musical/stylistic label, the term was also an apt characterization of the Zawinul Syndicate’s personnel and reflected on the band’s first album, The Immigrants (1988). According to Zawinul:

“It’s called The Immigrants because I realized that everybody [in the band], except for Scott and Cornell, is an immigrant. I’m an Austrian citizen. Acuna is a Peruvian Indian. Abraham Laboriel is from Mexico City. Rudy Regalado is from Venezuela.”3

Personnel selection in the Zawinul Syndicate was ultimately musically based – but over time, musical considerations also led to Zawinul’s divided opinion on the contemporary jazz scene. His chief criticism involved the scene’s strong retrospective tendencies; as he states in a 2003 interview with the noteworthy title “Die Amerikaner sind stehen geblieben” (The Americans Have Stopped Moving Forward):

[Interviewer:] “The bands with which you yourself wrote jazz history were all made up of American musicians. Odd – now you come to Zurich with musicians from Calcutta, Puerto Rico, Belgium, Mauritius. [Zawinul:] Well, these people play my music best. The Americans have stopped moving forward. Many have gone back to bebop, and I can’t do anything with that anymore. It’s largely the fault of record labels in the USA: they had no orientation, so they forced young jazz musicians to play bebop. That’s how it came to be this retrospective music. But everything in music, in art generally, has to come from people. It can’t just be an imitation.”4

Zawinul’s abandonment of contemporary jazz began well before the Zawinul Syndicate; it had its roots at least as far back as 1979, as bassist Percy Heath attests:

“I met Joe Zawinul in Austria. He is an Austrian musician. He went through a period of playing jazz music. Then he was sort of funky jazz, country jazz with Cannonball, which was at that time very popular. Now he has made this change to the big synthesizer. You know, he doesn’t claim it to be jazz, but they put it the jazz category. He doesn’t claim that anymore. He said, “Man, I ain’t playing no jazz.” He told me this down in Cuba. He said, “I want people to come see us like it’s a movie, and the music is the background for the spectacle.” I said, “Oh, I’m glad you told me that, Joe, because I failed to connect your music with jazz.”5

Thus, the starting point for this study of the Zawinul Syndicate’s musical style is framed by a few basic factors: Zawinul is concerned with his own, very personal, music; this music can be considered “world music” – and specifically does not belong to the category of jazz, at least in its current, “modern” form. This study will attempt to add to these few puzzle pieces in order to form a clearer picture of the almost twenty-year period of Joe Zawinul’s work with the Zawinul Syndicate – a period which, in spite of the singular quality of the music it produced, has to this point inspired only a handful of relevant papers.

The following summary outlines the most prominent characteristics of the Zawinul Syndicate’s music: repertoire, groove, musical density, harmony and sound. In addition, cross-references to Zawinul’s pre-1988 works are provided, showing the Zawinul Syndicate as a logical development within Joe Zawinul’s complete body of work.

(1) Repertoire

Between 1988 and 2007, six albums were released under the name “The Zawinul Syndicate”: The Immigrants (1988), Black Water (1989), Lost Tribes (1992), World Tour (1998), Vienna Nights (2005) and 75th (2007). In addition, 1989 saw the release of a DVD featuring a live concert from Philharmonic Hall in Munich. Zawinul’s other releases during this time period were either under his own name or as a sideman on other musicians’ albums.

On the six albums released by the Zawinul Syndicate, 65 discrete pieces appear. A number of these were recorded multiple times, bringing the total of released pieces to 74.

Joe Zawinul is listed as the author or co-author of 53 of these 65 titles. Only five of the 65 are by neither Zawinul nor his band members, of which three are jazz standards. The following table shows the exact figures:

| Criterion | Number (percentage) |

| Total number of individual pieces | 65 (= 100%) |

| Zawinul as author or co-author | 53 (= 81,54%) |

| Zawinul as only author | 44 (= 67,69%) |

| Other band member as author | 7 (= 10,77%) |

| Other band member as co-author with Zawinul | 9 (= 13,85%) |

| Non-band member as author | 5 (= 7,69%) |

Clearly, Zawinul’s role as primary composer for the Zawinul Syndicate is unchallenged. None of his collaborators appears as author or co-author more than twice on a single record – and the continual change of personnel in the band precluded any other members from expanding their role. This is a marked departure from Weather Report’s repertoire: membership remained largely constant over the life span of that band and in addition to Zawinul both Wayne Shorter and Jaco Pastorius contributed a large number of compositions.

A comparison of the repertoires of Weather Report and the Zawinul Syndicate reveals 12 pieces recorded by both bands:6

| Title | Year(s) recorded by Weather Report | Year(s) recorded by The Zawinul Syndicate |

| Badia | 1975, 1975, 1976, 1978, 1979, 1984 | 2004, 2007 |

| Birdland | 1976, 1976, 1978, 1979, 1979, 1982, 1984 | 1989 |

| Boogie Woogie Waltz | 1973, 1973, 1973, 1975, 1979 | 2004, 2007 |

| Carnavalito | 1985 | 1989, 1997 |

| Country Preacher | 1969, 1970 | 1992 |

| Fast City | 1980, 1980, 20027 | 2007 |

| In A Silent Way | 1969, 1969, 1970, 1973, 1978, 1979, 2002 | 1991, 2007 |

| It’s About That Time | 1969, 1973 | 1991 |

| Madagascar | 1980 | 2007 |

| Mercy, Mercy, Mercy | 1966, 1966, 1969 | 1988 |

| Scarlet Woman | 1974, 1975, 1976, 1978, 1979 | 2007 |

| Two Lines | 1976, 1983, 2002 | 1997, 2004, 2007 |

These 12 pieces were recorded a total of 18 times; roughly a quarter of those recorded by the Zawinul Syndicate had been recorded previously by Weather Report. However, the particular significance of the album 75th must be taken into account in this interpretation of the data: Technically a Zawinul Syndicate album, it is a live concert played on the occasion of Joe Zawinul’s 75th birthday and as such retrospectivity likely played a major role in the selection of material for the concert; seven Weather Report numbers were performed during the concert, three of which had never been previously recorded by the Zawinul Syndicate.

These overlappings in repertoire raise the question of how the stylistic approaches of the two groups differ in their performances the same piece. A representative comparison of the recordings of “Badia” in 1978 and 2004 show an astounding similarity. The drum performance from the 2004 recording is denser and more concise and Zawinul uses the Vocoder, typical for the Zawinul Syndicate – but the 1978 recording also features a synthesizer sound similar to a human voice. However, the earlier recording includes quasi-experimental passages, reminiscent of the early 1970s, which are eschewed by the Zawinul Syndicate.

(2) Groove

Groove, in the sense of a “persistently repeated pattern”8, represents both the basis and a significant part of the Zawinul Syndicate’s music. Joe Zawinul’s statement that “The groove comes first for me. Without it I don’t play.”9 is supported by the fact that nearly all of the awinul Syndicate’s faster pieces – three-quarters of its entire repertoire – are groove-based.

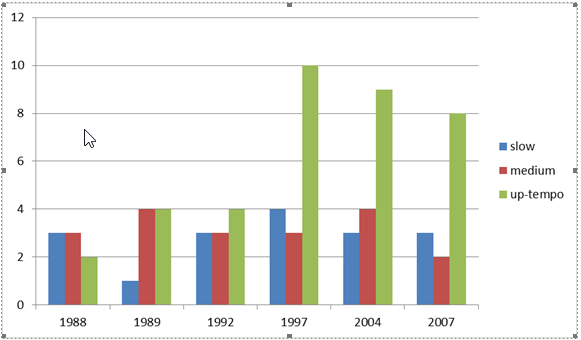

The groove pieces can be divided into two basic categories: up-tempo (80 bpm) and without clear repetition of a pattern. The following diagram shows the frequency of these three tempo areas on the Zawinul Syndicate’s six albums.

Between 1988 and 1992, as the graph shows, a relative parity of the three tempo classes was the rule. The later recordings tend toward faster tempi and beginning in 1997 such tempi clearly took precedence.

(3) Musical density

In the music of the Zawinul Syndicate, musical density – defined as the number of musical events per unit of time – rose to a level never reached by Weather Report, largely due to a high pitch of virtuosic activity by drummers and percussionists.10 An additional increase in density is provided by atmospheric elements, including (a) the ostinatic period of guitar and bass riffs, (b) the contrasting sweep of synthesizer pads and (c) the particular catchiness of main themes of the respective pieces, determined by concise, leitmotif-like patterns carefully arranged by Zawinul himself.11

In sum, this mixture of elements gives an impression of simplicity that was always of particular importance to Zawinul:12

“My parents never liked my music, but I love them and value them a great deal and I said to myself: “If I can’t play for my parents, I’m not a musician.” I wanted to make music that I could play for my parents, but that might also play in Harlem.”13

Zawinul emphasizes that complex construction and simple receivability need not be mutually exclusive:

“My music is complicated to play, but simple to listen to. That’s the secret. Cannonball Adderley once told me: “You write such difficult music, but when you play it – it’s clear.”14

This simplicity for the listener is due in no small part to the extraordinary musical density emanating from the rhythm section, which can impart a feeling of timelessness.15 In contrast to conventional, “unchanging” sounds, the Zawinul Syndicate’s music contains layers of sound that, due to their internal movement, carry enormous amounts of musical energy. The effect of this energy, in turn, is further intensified and takes on added density through Joe Zawinul’s highly specific instructions to his musicians regarding the microrhythmic performance of his grooves.16

(4) Harmony

The most immediately obvious aspect of the Zawinul Syndicate’s harmony is its particular transparency for the listener. Joe Zawinul achieved this effect (a) through the use of only a few simple harmonies,17 often in major keys,18 and (b) by ending more complex harmonic movements in simple harmonies or chord progressions.19 More intricate harmonic material, as in Weather Report recordings from 1971/72 – for instance pieces such as “Unknown Soldier” and “Crystal” – vanished almost completely by 1973.20

(5) Sound

The marked recognizability of the Zawinul Syndicate’s music owes much to Zawinul’s use of warm synthesizer sounds, in both his solos and accompaniment. In place of the soprano saxophone familiar from Weather Report recordings, he tends to substitute a similar sound generated on the Korg Pepe, a synthesizer designed specifically for him; the Vocoder and various sample sequences are also of great significance in this context. The basis for these tendencies is Zawinul’s particular affinity for everything having to do with sound. In response to the question of what inspires him, Zawinul states:

“The sound of my musicians. I have to hear how someone plays, what kind of tone he has, then pieces occur to me based on that. Even as a boy of eight or nine I was already interested in sound. I’d often go to a billiard hall with a friend of my father’s. Once there was an old piece of felt from one of the tables lying on a chair; I glued it into my accordion and got a sound that I later used on “Black Market” with Weather Report. That’s a genuine, original Zawinul sound.”21

Zawinul makes it clear that, for him, sound has a much higher value than many other skills possessed by well-educated, modern musicians:

[Interviewer:] “Why are there no jazz bands like that anymore? [Zawinul:] Jazz isn’t entertainment anymore. The young guys can play really well, but they’ve forgotten that music is also supposed to be entertainment. That’s why jazz is in decline. [Interviewer:] When you say ‘guys’ do you mean the ‘Young Lions’ – like the trumpeter Roy Hargrove or the saxophonist Joshua Redman? [Zawinul:] Yes. They play damned well. They play with Wynton Marsalis. He’s a fantastic musician and a great character, a really nice guy. I like him. He’s also a great musician. He can play Haydn, Gluck, he can play everything. But somehow for me nothing sticks. That was different with us – you always knew when Zawinul, or Wayne, or Jaco was playing. With Miles and Armstrong you knew who was playing after two notes. That doesn’t exist anymore – but that’s what the audience wants.”22

In the creation of sounds, Zawinul relies completely on his intuition; he emphasizes the essential connection to the human voice and language in his musical expression:

“[…] pure instinct. There’s nothing to say about that. When I hear a sound that I like to play with, the way the key feels, the way the sounds feel, then I modulate that sound to the point where it really rings like it is my voice, like it is my language. If I can do that, I know I can make some music. I couldn’t play with sounds that are not my sound.”23

This pursuit of individualism began to drive Zawinul’s work by the mid-1960s but reached its zenith in the Zawinul Syndicate, a premise borne out not only by the Zawinul Syndicate’s recordings but also on studio albums such as Faces and Places (2002), recorded under Zawinul’s own name, and the Zawinul-produced Salif Keita album Amen (Mango 261694, 1991).

Conclusion

The groundwork for the Zawinul Syndicate’s music was laid by Joe Zawinul’s development over the three and a half decades preceding the band’s founding. The 1974 recording “Nubian Sundance”, featuring a wealth of stylistic elements anticipating the work of the Zawinul Syndicate, offers a striking demonstration of this development;24 equally impressive is the quality of Zawinul’s ballad playing, documented as early as 1957. Thus, the later phases of Zawinul’s 55-year musical career are clearly built on that which came earlier. However, from the mid-1960s on, in keeping with Zawinul’s character, his focus shifted increasingly towards efforts to realize his own musical concept rather than – as previously – the preservation and continuation of the jazz tradition. Zawinul’s perpetual dissatisfaction with his musical past and his desire to continue growing25 make the special value of the Zawinul Syndicate’s music even clearer: Rather than a simple continuation of a musical journey beginning with Fats Waller, Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith and Duke Ellington, leading later to bebop and eventually the music of Weather Report, the Zawinul Syndicate represents a crystallization and broadening of Joe Zawinul’s musical concept – and as such, a new high point of his life’s work.

Referenced Zawinul Recordings

1954–57 Joe Zawinul and the Austrian All Stars: His Majesty’s Swinging Nephews 1954–1957. RST-915492.

1961–71 Cannonball Adderley: Cannonball Plays Zawinul. Capitol Jazz 724359707020.

1963 Ben Webster / Joe Zawinul: Soulmates. Riverside OJCCD-109-2.

1966 Cannonball Adderley Quintet: Cannonball in Japan. Capitol Jazz CDP 7935602.

1971f. Weather Report: I Sing The Body Electric. Columbia 88697145472.

1972 Weather Report: Live in Tokyo. Leopard LCD 106-2.

1973 Weather Report: Sweetnighter. Columbia 88697145472.

1974 Weather Report: Mysterious Traveller. CBS CDCBS 80027.

1974 Weather Report: Night Passage. Columbia 88697145472.

1975 Weather Report: Live in Berlin 1975. MIG 80020 CD + DVD.

1976 Weather Report: Black Market. Columbia 4682102.

1978 Weather Report: Live in Offenbach 1978. MIG 80092 2CD.

1982 Weather Report: Weather Report. Columbia 4767522.

1983 Weather Report: Live in Cologne 1983. AOG 80052 CD.

1989 The Zawinul Syndicate: Black Water. Columbia 4653442.

1992 The Zawinul Syndicate: Lost Tribes. Columbia 4689002.

1997 The Zawinul Syndicate: World Tour. ESC Records ESC/EFA 03656-2.

2002 Weather Report: Live and Unreleased. Columbia/Legacy 5080582.

2004 The Zawinul Syndicate: Vienna Nights. BHM 4001-2.

2007 The Zawinul Syndicate: 75th. BHM 4002-2.

Notes:

- Max Dax: “Joe Zawinul”. Alert Nr. 8 (Oktober 2002–Februar 2003). German version available online at http://www.alertmagazin.de/alert.php?issue=8&content=zawinul (accessed on April 9, 2013).

- Cf. Andrián Pertout: “Joe Zawinul: Jazz Icon”. Mixdown Monthly Nr. 78 (Oktober 4, 2000). Available online at http://www.pertout.com/Zawinul.htm (accessed on April 9, 2013).

- Josef Woodard: “Joe Zawinul: The Dialects of Jazz”. Down Beat 55/4 (April 1988), p. 17. Cf. Georg Lenger: “Der Jazzmusiker, Komponist und Arrangeur Joe Zawinul: Biographie, Diskographie und Analyse seines späteren Schallplattenwerkes”. Diploma thesis, Universität für Musik und darstellende Kunst Graz, 1995, p. 157.

- Christoph Merki: “Die Amerikaner sind stehen geblieben”. tagesanzeiger.ch (October 28, 2003). German version available online at http://web.archive.org/web/20070920210501/http://www.tages-anzeiger.ch/dyn/news/popjazz/319401.html (accessed on April 9, 2013).

- Batt Johnson: What is this Thing Called Jazz? Insights and Opinions from the Players. San José (et al.): Writer´s Showcase, 2001, p. 41.

- Tom Lord: The Jazz Discography Online. West Vancouver 2001.

- The 2002 Weather Report album Live and Unreleased contains material recorded between 1975 and 1983.

- Barry Kernfeld: “Groove (i)”. The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, 2nd ed.. Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/J582400 (accessed April 9, 2013).