Abstract:

This paper aims first to analyze the music industries in Russia and in Poland to later compare them, in order to find similarities or differences. The analysis involves mostly the same types of data and historical aspects, just from two different perspectives: Russian and Polish. The elements represented within the paper include: the history of the appearance of the first CDs, record labels and their development within the Russian and Polish markets, the statistics related to the distribution of CDs, as well as an analysis of a problem of piracy and governmental actions that were taken (or not taken) in order to fight it within two countries.

Russian music industry

The music industry in Russia went through numerous changes throughout the years. In the 1980s, in the USSR the most popular medias were long-playing records (LP) and compact cassettes (MC), which were[1] manufactured by factories located throughout the Union in cities such as Moscow, Leningrad, Riga or Tbilisi. In 1989 89.1 million long-playing records, 11 million mg cassettes and 10.4 million singles were sold. When it comes to the compact discs on the other hand, even though they were developed in the beginning of 1980s, they were not mass produced in the USSR until the 1989, due to them being considered as a dual-use technology. First compact-disc factory opened thanks to a large investment from the state’s budget, and it had an area of more than 2000m2. More than 20 employees were trained at enterprises located in Germany and Sweden. The main equipment suppliers and the participants of the installation ended up being foreign companies from countries such as Germany, Sweden, Netherlands, Switzerland and Japan.

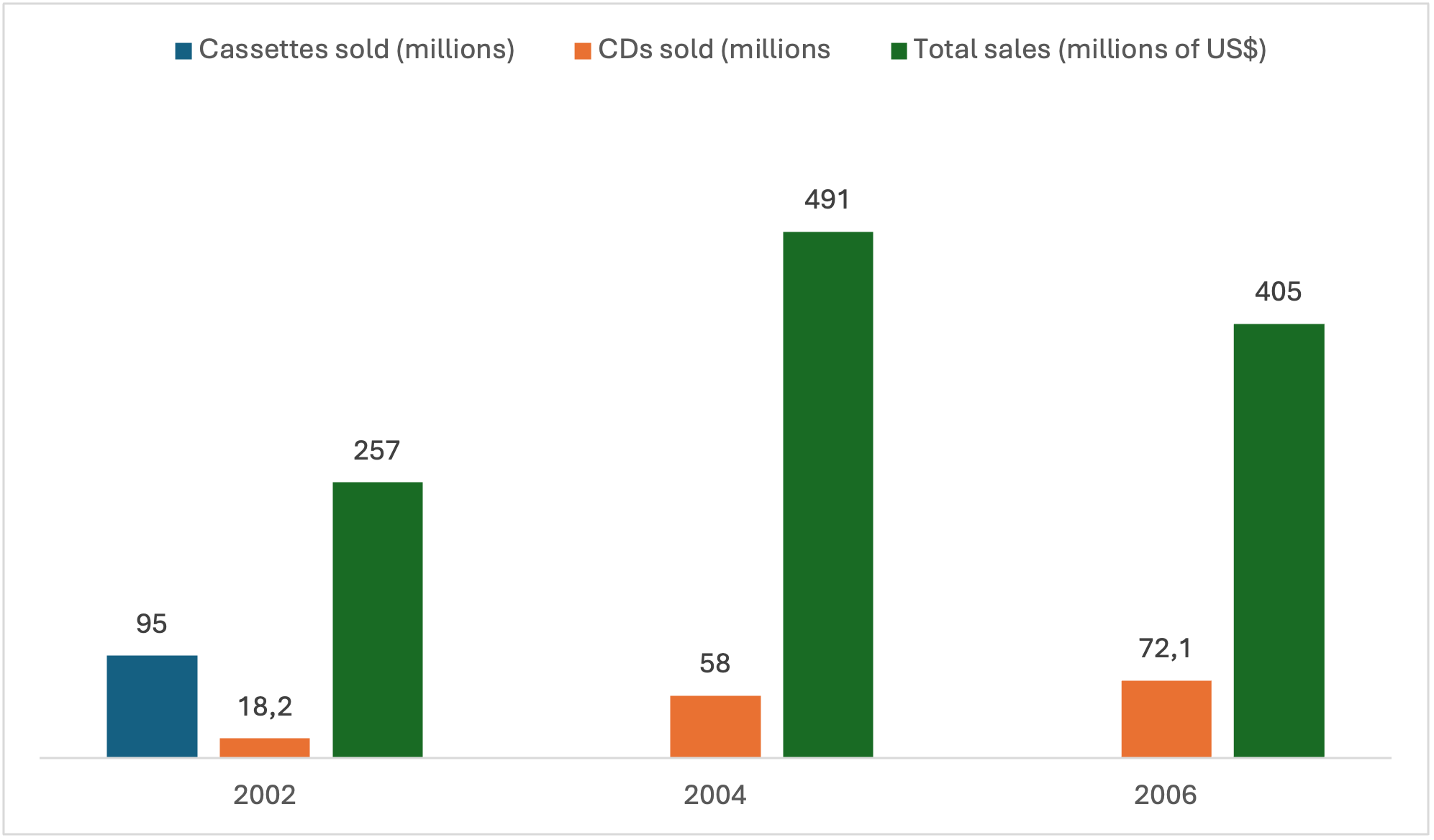

CDs quickly started gaining popularity on the Russian market over the years, but became affordable for the general public only within the course of 2000s. Growth of sales of CDs and the overall value of sales of the physical music within Russia can be trackable thanks to 3

annual reports by RIAJ (Recording Industry Association of Japan), that include data related to global sales of recorded music in Russia from 2002, 2004 and 2006.

In 2002[2] music in Russia was mostly sold on cassettes according to the report. There were 95 million sales of cassettes with music over the course of the year with only 18.2 million CD sales. The overall value of sales of all types of media was around 257 millions of US dollars.

Starting from the report including statistics from 2004[3], the data about the sales of cassettes is absent, but it is possible to track the growth of the CD market. Within that year there were 58 millions of compact-disc sales with an overall value of all types of music on physical media around 491 million US dollars.

In 2006[4] 72.1 million of compact-discs sales were recorded in Russia with an overall value of all the physical sales around 405 million US dollars.

The chart for better understanding is present:

Picture no. 1

Taken from the RIAJ Yearbooks from 2004, 2006 and 2008.

In the times of late Soviet Union “Melodiya” was the only officially existing record label within the country until the fall of the USSR[5]. It was founded in 1964 and had its record studios spread all around the Union. Since there were no other labels, it was a monopoly. After the fall of Soviet Union “Melodiya” undergone the process of demonopolization and decentralization throughout which its structures either gained independence or were shut down.[6]

After the fall of Soviet Union not only local record labels were joining the market. Widely known global record labels also slowly started entering Russia over the course of decades and started gaining their market share. Here are the examples of some of them:

Sony Music joined the market by opening its Russian department in 1999[7]. In September of 2022 record label decided to officially leave the country[8] and has removed all of its foreign music catalogues from Russian streaming services, due to the sanctions after the beginning of war in Ukraine. The company continued to represent local artists under the label “Kiss Koala”.

Warner Music officially entered the Russian market in 2013[9] after acquiring an already well-established local record label “Gala Records”, which was the first private music recording company (formed in 1988)[10], that already managed to acquire a lot of well-known artists from the region and was an official partner of EMI Music. In the March of 2022 Warner Music Russia stopped its operations on the territory of Russia, which later resulted in the creation of a company S&P Digital, that later started distributing the works of the frozen label on the streaming services.

These examples in connection to behavior of global music labels highlight the trend in the whole contemporary state of Russian music industry. Most artists that signed contracts with foreign labels and decided to stay within the Russian market are forced to find an alternative in the form of joining Russian music labels, in order to continue distributing their works.

Another contemporary global tendency that significantly affected Russia is the rise of streaming services, which leads to a growth of overall music consumption.[11] This can be seen thanks to a study “Musical consumption practices of Russians“ from 2022. That research had the study group of around 2000 people out of which 71% listen to music on a daily basis with 22% listening to music more often in comparison to last year. In total, 85% of those respondents listen to music without downloading it onto their devices. The streaming market is growing over the years, although that growth is challenging and faces many obstacles. For example, according to a study, in the beginning of 2022 the most popular streaming services on which users were purchasing paid subscriptions were Spotify (34%), Yandex.Music (22%), Youtube Music (17%), iTunes (16%).

After the geopolitical events in 2022 international companies started to rapidly leave the Russian market, and streaming services were not an exception. Out of this list the only streaming service that is fully accessible for the Russian audience from this list, and in which it is possible to legally purchase a subscription is a Russian service – Yandex.Music. It by 15 itself lost a number of recordings from foreign artists due to their boycott of streaming their music on a Russian market. For example, all the content of the band Pink Floyd was forcefully removed from the platform due to copyright holder’s will.[12] Global record labels, such as Universal Music, Warner Music and Sony Music stopped sharing all new releases with the platform from the March of 2022. These tendencies are making honest consumers of Russian music market more prone to look for other methods of listening to music that disappeared, including illegal methods, such as piracy.

The problem of piracy in Russia

In the beginning of 1990s, with the final fall of USSR the censorship was lifted, and artists were able to freely release their works without being censored or forced to be undercover.[13] Many local recording companies were formed and were rapidly developing on a fresh market becoming actual record labels and making contracts with artists by mass releasing their works on compact discs. However, there appeared a huge issue that is pushing back the development of the music industry market and that is substantially decreasing the earnings of musicians to this day – _piracy (the act of illegally copying a computer program, music, a film, etc. and selling it[14]), which was popularized long before the fall of the Soviet Union. Contemporary listeners from this region tend to select the products simply based on a quality/price basis, without taking into account the copyright or legality of such sales, especially since there was simply close to no legislation that would efficiently regulate or actually prohibit illegal distribution of copies. The sales were done right in the open without major consequences for the distributors. The market got completely flooded with pirated recordings, especially after the severe economic crisis in the 1998, the original and legal copies of recordings were sold for symbolic prices, in order to at least somewhat compensate the severe financial losses of the sellers, since they simply couldn’t compete with the market of pirated copies due to the challenging financial situation of average consumers of music.

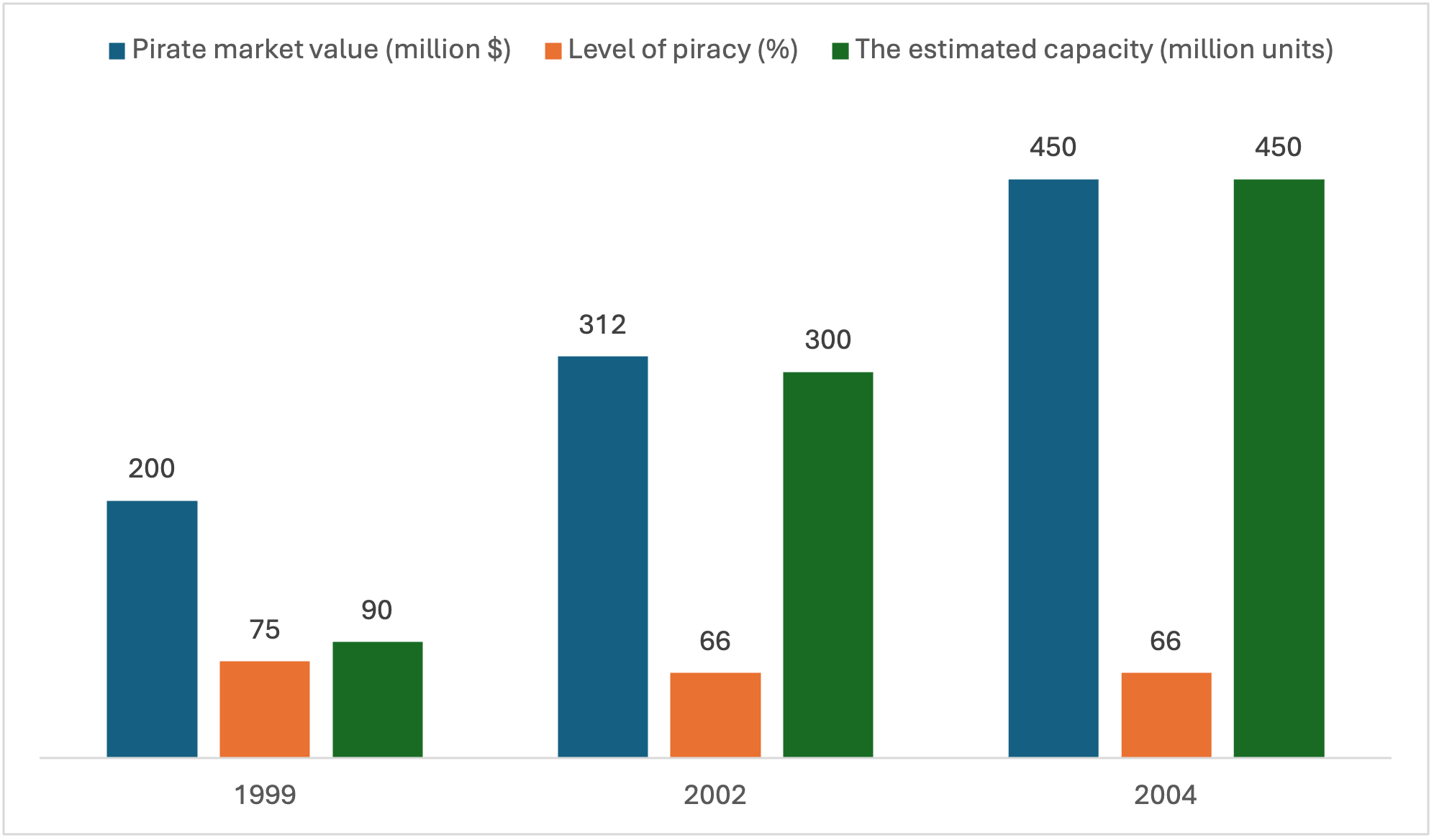

The issue of piracy, failure, or the lack of will of its efficient regulation by the government, its market growth, and the overall substantial increase of disc accessibility within Russia throughout these years are easily trackable thanks to International Federation of the Phonographic Industry’s yearly reports showcasing the statistics related to worldwide piracy with detailed information about problematic countries. 3 reports that were made by IFPI about Russia over the years were selected to clearly demonstrate the changes within the country in that sphere.

In 1999 Russia’s level of piracy was catastrophic: 75%, with piracy market valued at 200 million dollars, and Russia being the second most problematic country according to IFPI[15]. The estimated capacity, taking into account all disc formats, was around 90 million units.

In 2002 the share of pirated music on the market was still high, with the piracy level reaching 66% according to IFPI’s commercial piracy report[16]. In this report Russia was named as “Europe’s most serious piracy problem territory” with the pirate market valued at 312 million dollars. The estimated capacity rose significantly and reached 300 million units, showcasing the significant increase in the accessibility of discs.

According to the IFPI’s report from 2005[17] the situation in Russica related to piracy didn’t get substantially better. Federation states that from 2002 to 2004 there were 12 raids conducted by Russian law enforcement agencies on the compact disc plants, out of which only four resulted in at least some charges pressed, which were only conditional sentences. That can indicate an uninterest of Russian authorities in actively fighting the pirates. The estimated capacity continued to rapidly rise making around 450 million units. The pirate market value was around 450 million dollars, and the piracy level was considered to be around 66%.

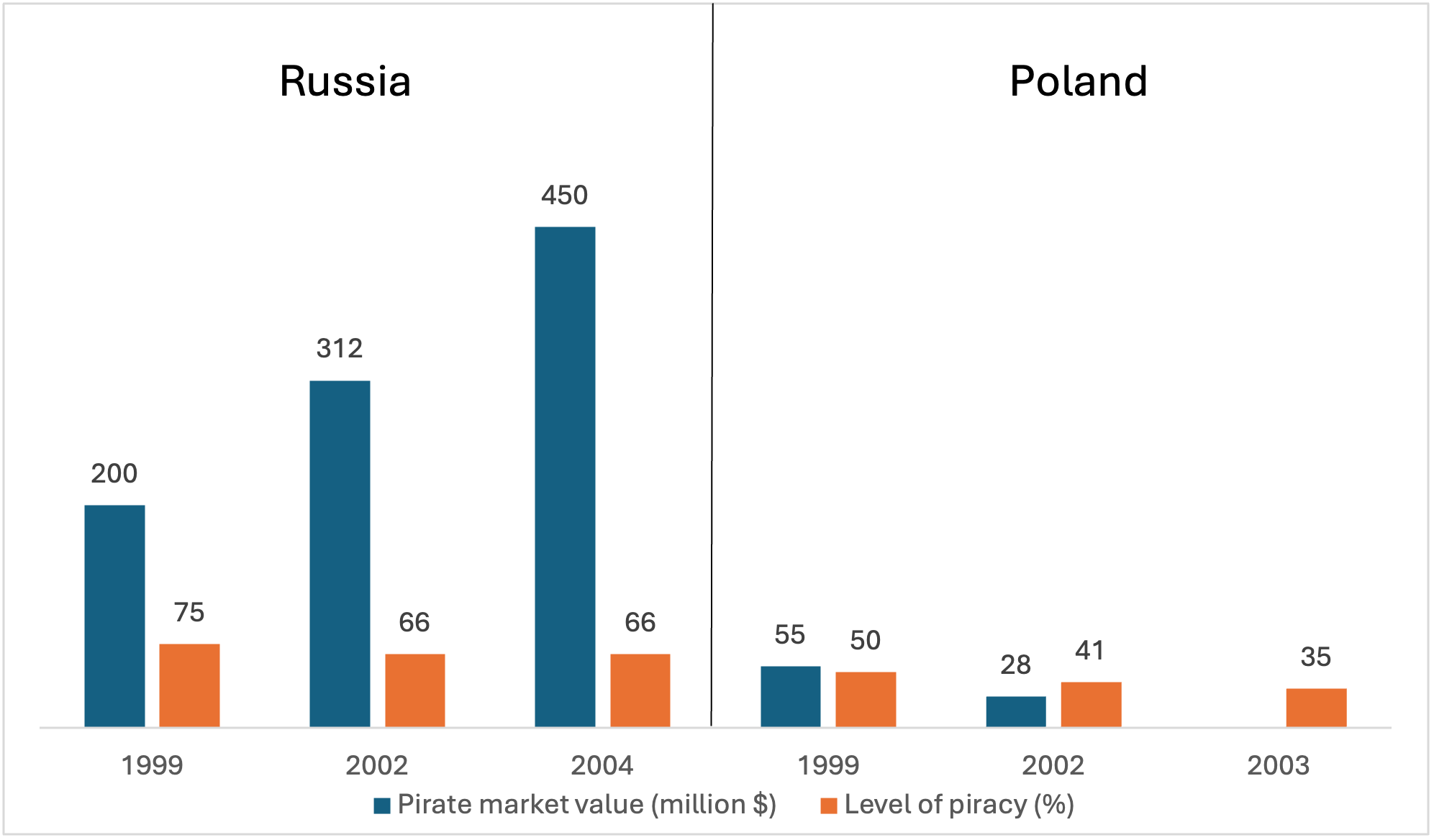

For better understanding of the statistics the graph about those 3 selected years in relation to Russian piracy is present:

Picture no. 2

Taken form the IFPI’s data[18] related to Russia within commercial piracy reports from 2000, 2003 and 2005.

With the popularization of internet and rapid digitalization of piracy and spreading of file-exchanging platforms, it’s getting harder to estimate the value of Russian market of music piracy. In contemporary times, according to the survey conducted by Russian Public Opinion Research Center (VCIOM) in 2018[19], 71% of Russians think that the current level of income in the country is insufficient to demand payment from Russians for viewing and downloading

various types of video and audio content, which indicates that the potential level of demand for piracy is still substantially high in the society.

Piracy music market might also increase its share after the year of 2022, due to geopolitical events associated with Russia and challenging situation on the music market. The study “INTERNET IN RUSSIA in 2022-2023: status, trends and development prospects”[20] conducted by Electronic Communications Association (RAEC) states that after the inaccessibility of popular music streaming services such as Apple Music, Spotify and YouTube Music and the seizure of catalogs of big players on the market, such as Sony Music Group from the Russian platforms, around 14% of former users of streaming services switched to pirate resources, referring to the study by the researcher Kantar[21].

Another interaction of politics and piracy within Russia can be spotted in our days based on the case of the biggest Russian torrent tracker[22] “rutracker.org” that stores more than two million torrents on the website. Russian authorities were not blocking access to the website for the longest time, the service first appeared in 2004[23] under the domain name “torrents.ru”, and swiftly gained its popularity, having 4 million users visiting the website monthly in 2010, only in 2010 the original website address was blocked by Russian authorities, which led to the administration of the torrent tracker simply moving to another domain, namely “rutracker.org”. The piracy resource continued to gain its popularity and existed without any major sanctions until 2015, where the court after the review of another out of many complaints regarding the violation of copyright, associated with that torrent tracker, finally stated that the access to the domain will be blocked in Russia.[24] In March of 2022 Russian users of internet started to report that previously blocked website started to open from the territory of Russia without any usage of measures to bypass the restrictions.[25] That happened after one of State Duma deputies offered to unblock the website.

Polish music industry

Production of compact discs in Poland started by the end of 1980s. First Polish compact disc was released in January of 1988.[26] It carried a name of “Chopin Tausig Wieniawski – koncerty fortepianowe“, the album contained a recording of the piano concerto in E minor, Op. 11 by Fryderyk Chopin and the piano concerto op. 20 by Józef Wieniawski, performed by the Baltic Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra[27]. The disc was issued by a Polish record label “Przedsiębiorstwo Nagrań Wideo-Fonicznych Wifon”, main activities of whichinvolved publishing, producing and trading in the field of audio cassettes and records.[28]

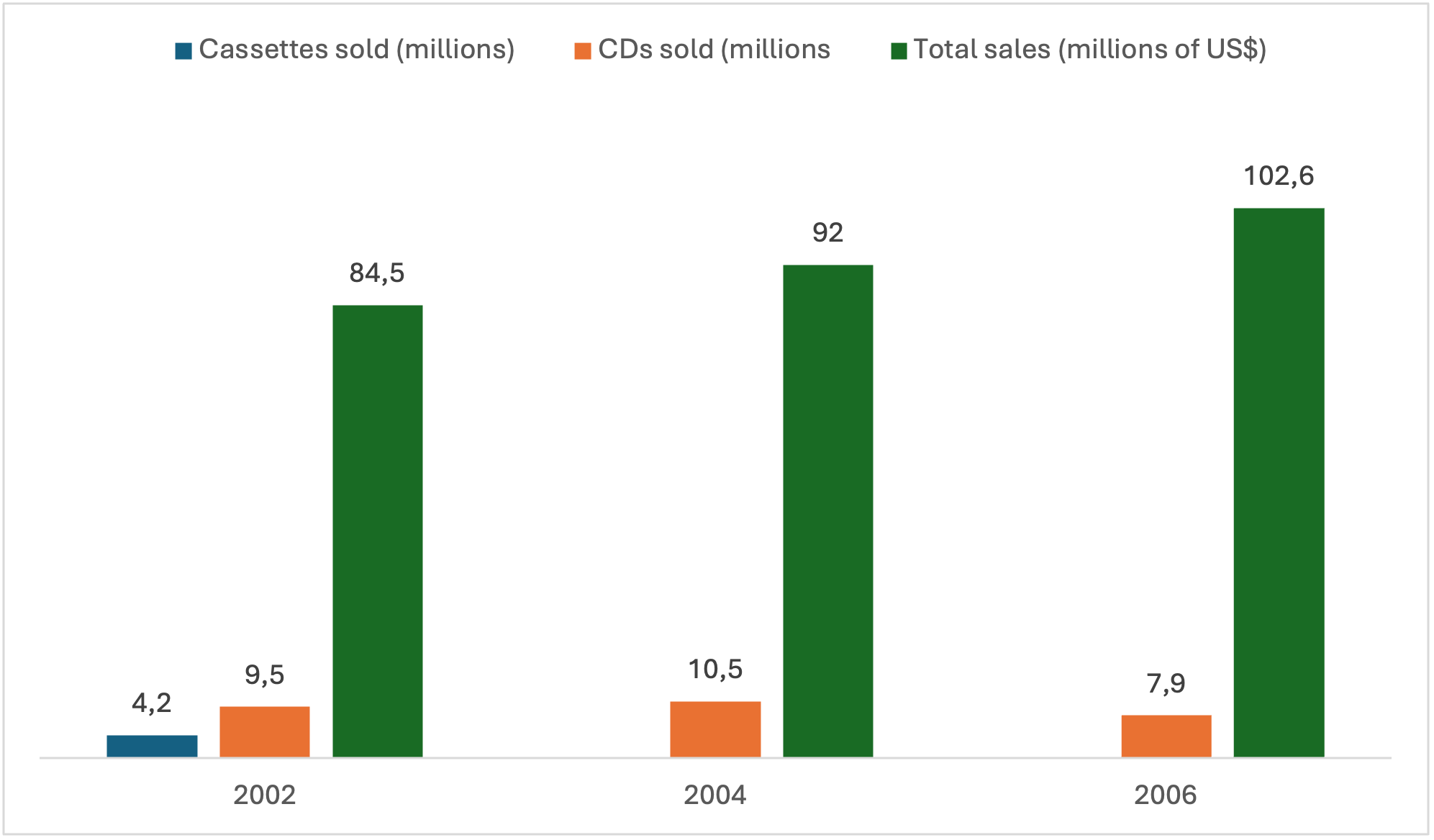

CDs quickly gained popularity on Polish market and were the bestselling music carriers in 2000s. Growth of sales of CDs and the overall sales value of the physical music within Poland can be tracked thanks to 3 annual reports by RIAJ (Recording Industry Association of Japan) that include data related to global sales of recorded music in Poland from 2002, 2004 and 2006.

Data from 2002[29] includes the number of cassettes sales, CDs and the overall sales value of all types of media on Polish market within the year. In 2002 CDs were already more popular than cassettes on Polish market. There were only 4.2 million of cassettes with music sold. The amount of sales of musical CDs was substantially higher with around 9.5 million units sold. The overall value of sales of all types of media was estimated at 84.5 million US dollars.

From 2004[30] the data about the sales of cassettes in Poland is absent, however the growth of sales of CDs is still easily trackable. Within that year there were approximately 10.5 million CDs sold on Polish market. The total value of sales was around 92 million US dollars.

In 2006[31] the amount of sold CDs decreased with around 7.9 million units sold. The total market value of sales of all types of media on the other hand increased, and reached 102.6 million US dollars.

For better understanding the chart with all the abovementioned data is present:

Picture no. 3

Taken from the RIAJ Yearbooks from 2004, 2006 and 2008[32].

On the example of Wifon, a company that manufactured first Polish compact disc, we can see the unfortunate fate of many companies in the sphere of music throughout the process of rebuilding and restructuring of the state. After the fall of the communist regime “Wifon” turned out not to be a profitable body and had to undergo a recovery program, which started in March of 1992 and continued all the way until 1995, by which it had a pending liability of more than a millinon zł. with solely negative income over the previous years. In the same year it was agreed that it would have to follow a path of “quick sale”, which did not turn out as a succes due to inability to find a buyer, and in the year of 1997 all the company’s_ assets were auctioned.[33]

Record labels

After the fall of Polish People’s Republic global music labels started joining the newly formed market and forming oligopoly. Here are examples of some of them:

Warner Music Poland entered the Polish market in 1994 after acquiring a record company Polton, which was functioning from 1983. In 2013, the Warner Music Poland label absorbed Parlophone Music Poland (previously known as EMI Music Poland until 2013), and in 2015 it bought Polskie Nagrania Muza – the oldest Polish record label.[34]

Sony Music Entertainment Poland entered the market in 1995 after acquiring an already established Polish record label MJM Music PL.[35] Later, in 2003 MJM Music PL was rebought and reestablished, and continued functioning as an independent entity.[36]

According to the report from 2008, 75% of the Polish market was dominated by the four global major record labels (Universal Music Polska, EMI Music Poland, Sony BMG Music Entertainment and Warner Music Poland).

These numbers can highlight that the sphere of record labels in Poland can be considered as oligopolistic with a heavy influence of international giants.

The problem of piracy in Poland

Contemporary Polish consumers have free access to the music market, however, piracy is still a severe problem that the Republic of Poland is trying to deal with throughout its existence.

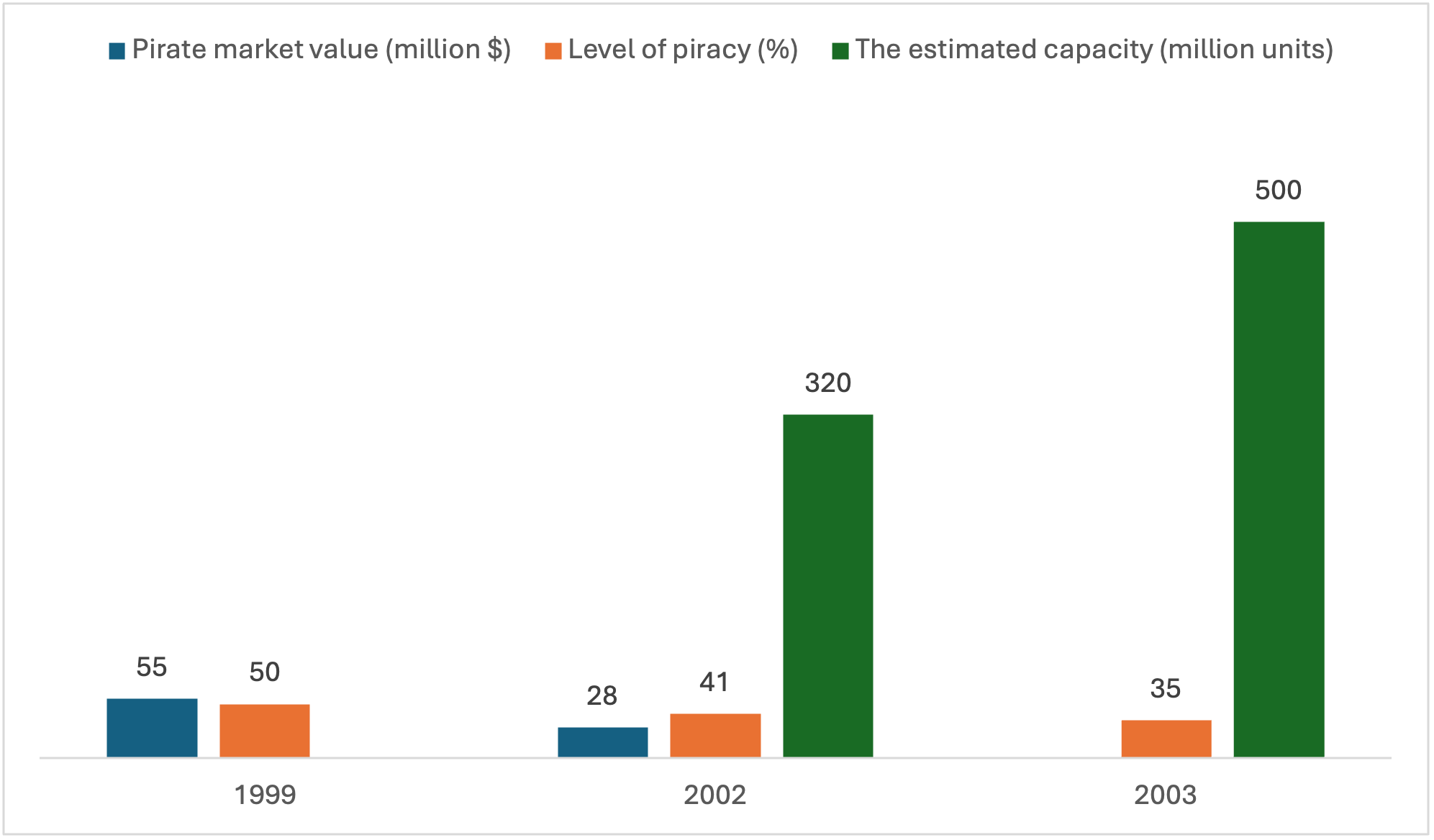

The issue of piracy in Poland throughout the years is easily trackable thanks to International Fedederation of the Phonographic Industry’s yearly reports showcasing the statistics related to worldwide piracy with detailed information about problematic countries. 3 reports made by IFPI about Poland over the years were selected, in order to clearly demonstrate the changes within the country in that sphere.

In 1999 Poland was a part of IFPI’s top 10 prioritized countries in terms of domestic piracy levels. Piracy level averaged around 50% with the pirate market valued at around 55 million dollars.[37]

According to the IFPI’s report 2002 Polish piracy level got better in comparison to previous reports, with some regulations being in place. The piracy level was considered to be around 41% with the pirate market being valued at 28 million dollars. The estimated capacity was graded at around 320 million units.[38]

In the report from 2004[39] IFPI noted that Poland made a progress in fighting piracy thanks to the implementation of a good law regarding optical discs, after which the country was removed from the company’s priority lists. A piracy level was estimated to be within 25-50% with a disc capacity of 500 million units.

These 3 studies show that Poland managed to successfully fight with piracy thanks to an active governmental participation.

For better understanding of the statistics the graph with available data about those 3 selected years in relation to Polish piracy is present:

Picture no.4

Taken from the IFPI’s data[40] related to Poland within commercial piracy reports from 2000, 2003 and 2004.

Conclusion and comparison

Based on the analysis of the Russian and Polish music markets, a conclusion can be drawn: the initial conditions and patterns in both countries at the time from which the research starts were quite similar. For example the time period of first compact-disc release, the fate of previously state-owned music labels, the phenomenon of globalization and oligopolistic giants entering the market. However, after some time the two music markets started to develop in completely different ways. Poland was systematically and progressively moving over the years towards becoming a full-fledged and rule-abiding part of the global music market. Russia, unfortunately, due to geopolitical circumstances, is quite rapidly turning its music market into a fairly closed structure, that is slowly separating from the global music industry. There is a huge lack of governmental interest towards taking legal actions against pirates and making copyright laws function efficiently. The graph clearly shows that if Poland and its government consistently and thoughtfully fought the problem of piracy and achieved success, then in Russia inefficient and indecisive steps clearyl didn’t lead to tangible results.

Picture no. 5

Taken from the IFPI’s data related to Poland and Ruzssia within commercial piracy reports from 2000, 2003, 2004 and 2005.

Bibliography (selection):

Баулин, Александр: Торренты попали под раздачу Путь RuTracker: от народной славы до пожизненной ссылки [Baulin, Aleksandr: Torrenty popali pod razdachu Put’ RuTracker: ot narodnoj slavy do pozhiznennoj ssylki], in “Lenta.ru”, 2015, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://lenta.ru/articles/2015/11/10/torrentway/

Бояринов, Денис: Сергей Кузнецов: «Важен _красивый _мотивчик _в _миноре» [Boyarinov, Denis: Sergej Kuznecov: «Vazhen krasivyj motivchik v minore»], in “Colta.ru”, 2008, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://os.colta.ru/music_modern/names/details/2444/

Brzostek, Dariusz: Zmiana ustroju, zmiana nośnika? Digitalizacja dźwięku i praktyki polskich fonoamatorów w czasach transformacji in “Instytut Nauk o Kulturze, Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika“, 2022, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://czaskultury.pl/wpcontent/uploads/2021/03/DBrzostek_ZmianaUstrojuZmianaNosnika_CzasKultury_3_2020.pdf

Давыдов С.Г., Казарян К.Р., Сайкина М.В: Интернет в России в 2022-2023 годах состояние, тенденции и перспективы развития, отраслевой доклад [Davydov S.G., Kazaryan K.R., Sajkina M.V: Internet v Rossii v 2022-2023 godah sostoyanie, tendencii i perspektivy razvitiya, otraslevoj doklad], 2023, Дизайн-студия RE-FORM, 2023, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://raec.ru/upload/files/internet-in-rus-22-23.pdf

Лебедева, Валерия – Тишина, Юлия: От Sony Music останется «Коала» [Lebedeva, Valeriya – Tishina, Yuliya: Ot Sony Music ostanetsya «Koala»], in “Коммерсантъ”, 2022, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5549427

Напреенко И., Рондарев А., Практики музыкального потребления россиян. Основные особенности и тренды, М.: Институт исследований культуры НИУ ВШЭ, 2022 [Napreenko I., Rondarev A., Praktiki muzykal’nogo potrebleniya rossiyan. Osnovnye osobennosti i trendy, M.: Institut issledovanij kul’tury NIU VSHE, 2022]. ISBN 978-5-6046913-6-6, [online]

https://publications.hse.ru/pubs/share/direct/560621998.pdf

Наумова, Евгения: В России вновь заработал RuTracker [Naumova, Evgeniya: V Rossii vnov’ zarabotal RuTracker], in “Lenta.ru“, 2022 [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://lenta.ru/news/2022/03/05/rutracker/

Рейн, Алиса: «Яндекс» и VK оставят без западной музыки [Rejn, Alisa: «Yandex» i VK ostavyat bez zapadnoj muzyki], in “ADPASS”, 2022, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://adpass.ru/yandeks-i-vk-bez-muzyki/

Щербакова, Катя: Когда мировая борьба с файлообменными сетями доберется до России? [Sherbakova, Katya: Kogda mirovaya bor’ba s fajloobmennymi setyami doberetsya do Rossii?], in “Online812”, 2009, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20220406024218/https://online812.ru/2009/05/12/002/

Тихонов, Александр: Компакт-диск в России самое начало… [Tihonov, Aleksandr: Kompakt-disk v Rossii samoe nachalo…], in “Звукорежиссер”, 2005, [online] retrieved 10 April 2024,

https://web.archive.org/web/20131126195409/http://rus.625net.ru/audioproducer/2005/03/cd.htm

[1] Тихонов, Александр: Компакт-диск в России самое начало… _[Tihonov, Aleksandr: Kompakt-disk v Rossii samoe nachalo…], in “Звукорежиссер”, 2005, [online] retrieved 10 April 2024,

https://web.archive.org/web/20131126195409/http://rus.625-net.ru/audioproducer/2005/03/cd.htm

[2] RIAJ Yearbook 2004, The Recording Industry in Japan, Statistics, Analysis Trends, 2004, [online] retrieved 10 April 2024,

https://www.riaj.or.jp/riaj/pdf/issue/industry/RIAJ2004E.pdf

[3] RIAJ Yearbook 2006, The Recording Industry in Japan 2006, 2006, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://www.riaj.or.jp/riaj/pdf/issue/industry/RIAJ2006E.pdf

[4] RIAJ Yearbook 2008, The Recording Industry in Japan 2008, 2008, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://www.riaj.or.jp/riaj/pdf/issue/industry/RIAJ2008E.pdf

[5] Мелодия, О Мелодии [Melodiya, O Melodii], [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://melody.su/melody/about/

[6] Справочно-информационный портал dic.academic.ru, Энциклопедический справочник. — М.: Большая Российская Энциклопедия. 1992, Москва [Spravochno-informacionnyj portal dic.academic.ru, Enciklopedicheskij spravochnik. — M.: Bol’shaya Rossijskaya Enciklopediya. 1992, Moskva], [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://dic.academic.ru/dic.nsf/moscow/1810/%C2%AB%D0%9C%D0%B5%D0%BB%D0%BE%D0%B4%D0%B8%D1%8F

[7] Лебедева, Валерия – Тишина, Юлия: От Sony Music останется «Коала» [Lebedeva, Valeriya – Tishina, Yuliya: Ot Sony Music ostanetsya «Koala»], in “Коммерсантъ”, 2022, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/5549427

[8] Из российских стриминговых сервисов пропадут треки Элвиса Пресли, Селин Дион, Бритни Спирс, Майкла Джексона и многих других исполнителей. Sony Music_ полностью уходит из России [Iz rossijskih strimingovyh servisov propadut treki Elvisa Presli, Selin Dion, Britni Spirs, Majkla Dzheksona i mnogih drugih ispolnitelej. Sony Music polnost’yu uhodit iz Rossii,], in “iXBT.com”, 2022, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://www.ixbt.com/news/2022/09/08/iz-rossijskih-strimingovyh-servisov-propadut-treki-jelvisa-presli-selin-dion-britni-spirs-majkla-dzheksona-i-mnogih.html

[9] Ibid.

[10] Бояринов, Денис: Сергей Кузнецов: «Важен _красивый _мотивчик _в _миноре» [Boyarinov, Denis: Sergej Kuznecov: «Vazhen krasivyj motivchik v minore»], in “Colta.ru”, 2008, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://os.colta.ru/music_modern/names/details/2444/

[11] Напреенко И., Рондарев А., Практики музыкального потребления россиян. Основные особенности и тренды, М.: Институт исследований культуры НИУ ВШЭ, 2022 [Napreenko I., Rondarev A., Praktiki muzykal’nogo potrebleniya rossiyan. Osnovnye osobennosti i trendy, M.: Institut issledovanij kul’tury NIU VSHE, 2022]. ISBN 978-5-6046913-6-6, [online]

https://publications.hse.ru/pubs/share/direct/560621998.pdf

[12] Рейн, Алиса: «Яндекс» и VK оставят без западной музыки [Rejn, Alisa: «Yandex» i VK ostavyat bez zapadnoj muzyki], in “ADPASS”, 2022, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://adpass.ru/yandeks-i-vk-bez-muzyki/

[13] Единая _система _идентификации _легальных _экзампляров _аудио- и _видеопродукции _[Edinaya sistema identifikacii legal’nyh ekzamplyarov audio- i videoprodukcii], in “Звукорежиссер”, 2004, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://web.archive.org/web/20121016120449/http://rus.625-net.ru/audioproducer/2004/01/pirat.htm

[14] Piracy, in Cambridge Business English Dictionary, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/piracy

[15] 15 IFPI Music. Piracy Report 2000, 2000, IFPI, 2000, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20081117004101/http://www.ifpi.org/content/library/Piracy2000.pdf

[16] The recording industry commerecial piracy report 2003, 2003, IFPI, 2003, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20081117004029/https://www.ifpi.org/content/library/Piracy2003.pdf

[17] The Recording Industry 2005 commercial piracy report, 2005, IFPI, 2005, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20101126165742/http://www.ifpi.org/content/library/Piracy2005.pdf

[18] IFPI Music. Piracy Report 2000, 2000, IFPI, 2000, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20081117004101/http://www.ifpi.org/content/library/Piracy2000.pdf

The recording industry commerecial piracy report 2003, 2003, IFPI, 2003, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20081117004029/https://www.ifpi.org/content/library/Piracy2003.pdf

The Recording Industry 2005 commercial piracy report, 2005, IFPI, 2005, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://web.archive.org/web/20101126165742/http://www.ifpi.org/content/library/Piracy2005.pdf

[19] Заплати за подписку — смотри спокойно? [Zaplati za podpisku — smotri spokojno?], in “ВЦИОМ НОВОСТИ”, 2018, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://wciom.ru/analytical-reviews/analiticheskii-obzor/zaplati-za-podpisku-smotri-spokojno-

[20] Давыдов С.Г., Казарян К.Р., Сайкина М.В: Интернет в России в 2022-2023 годах состояние, тенденции и перспективы развития, отраслевой доклад [Davydov S.G., Kazaryan K.R., Sajkina M.V: Internet v Rossii v 2022-2023 godah sostoyanie, tendencii i perspektivy razvitiya, otraslevoj doklad], 2023, Дизайн-студия RE-FORM, 2023, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://raec.ru/upload/files/internet-in-rus-22-23.pdf

[21] После ухода зарубежных аудиосервисов только 14% пользователей перешли на пиратские ресурсы [Posle uhoda zarubezhnyh audioservisov tol’ko 14% pol’zovatelej pereshli na piratskie resursy], in “Adindex“, 2022, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://adindex.ru/news/researches/2022/08/29/306293.phtml

[22] Щербакова, Катя: Когда мировая борьба с файлообменными сетями доберется до России? [Sherbakova, Katya: Kogda mirovaya bor’ba s fajloobmennymi setyami doberetsya do Rossii?], in “Online812”, 2009, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20220406024218/https://online812.ru/2009/05/12/002/

[23] Баулин, Александр: Торренты попали под раздачу Путь RuTracker: от народной славы до пожизненной ссылки [Baulin, Aleksandr: Torrenty popali pod razdachu Put’ RuTracker: ot narodnoj slavy do pozhiznennoj ssylki], in “Lenta.ru”, 2015, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://lenta.ru/articles/2015/11/10/torrentway/

[24] Информация по делу № 3-0647/2015 [Informaciya po delu № _3_-0647/2015], in “Суды общей юрисдикции города Москвы”, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://m.mos-gorsud.ru/mgs/services/cases/first-civil/details/f09a13e6-6da8-4932-9801-db9fb4ba8b58

[25] Наумова, Евгения: В России вновь заработал RuTracker [Naumova, Evgeniya: V Rossii vnov’ zarabotal RuTracker], in “Lenta.ru“, 2022 [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://lenta.ru/news/2022/03/05/rutracker/

[26] Brzostek, Dariusz: Zmiana ustroju, zmiana nośnika? Digitalizacja dźwięku i praktyki polskich fonoamatorów w czasach transformacji in “Instytut Nauk o Kulturze, Uniwersytet Mikołaja Kopernika“, 2022, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://czaskultury.pl/wpcontent/uploads/2021/03/DBrzostek_ZmianaUstrojuZmianaNosnika_CzasKultury_3_2020.pdf

[27] Wifon – WCD 001, Le Chant Du Monde – LDC 278 902.

[28] Jednostki podległe i nadzorowane przez przewodniczącego KRRiT, 1995, [online] retrieved 17 April 2024, https://web.archive.org/web/20171127043603/http://www.krrit.gov.pl/Data/Files/_public/Portals/0/sprawozdania/spr1996/spr1996_zal_a.pdf

[29] RIAJ Yearbook 2004, The Recording Industry in Japan, Statistics, Analysis Trends, 2004, [online] retrieved 10 April 2024, https://www.riaj.or.jp/riaj/pdf/issue/industry/RIAJ2004E.pdf

[30] RIAJ Yearbook 2006, The Recording Industry in Japan 2006, 2006, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://www.riaj.or.jp/riaj/pdf/issue/industry/RIAJ2006E.pdf

[31] RIAJ Yearbook 2008, The Recording Industry in Japan 2008, 2008, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024, https://www.riaj.or.jp/riaj/pdf/issue/industry/RIAJ2008E.pdf

[32] RIAJ Yearbook 2004, The Recording Industry in Japan, Statistics, Analysis Trends, 2004, [online] retrieved 10 April 2024

https://www.riaj.or.jp/riaj/pdf/issue/industry/RIAJ2004E.pdf

RIAJ Yearbook 2006, The Recording Industry in Japan 2006, 2006, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024 https://www.riaj.or.jp/riaj/pdf/issue/industry/RIAJ2006E.pdf

RIAJ Yearbook 2008, The Recording Industry in Japan 2008, 2008, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024 https://www.riaj.or.jp/riaj/pdf/issue/industry/RIAJ2008E.pdf

[33] Krajowa Rada Radiofonii i Telewizji, Krajowa Rada Radiofonii i Telewizji załącznik do Sprawozdania Krajowej Rady Radiofonii i Telewizji z rocznego okresu działalności, Warszawa, 1997, [online] retrieved 17 April 2024, http://www.archiwum.krrit.gov.pl/Data/Files/_public/Portals/0/sprawozdania/spr1997/spr1997_zal_c.pdf

[34] Polskie Centrum Informacji Muzycznej, wydawca Warner Music Poland, 2015, [online] retrieved 17 April 2024,

https://www.polmic.pl/index.php?option=com_mwinstytucje&view=wydawca&id=577&lang=pl

[35] Polskie Centrum Informacji Muzycznej, wydawca Sony Music Entertainment Poland, 2021, [online] retrieved 17 April 2024,

https://www.polmic.pl/index.php?option=com_mwinstytucje&view=wydawca&id=576&Itemid=0&lang=pl

[36] MJM Music PL, Historia, [online] retrieved 17 April 2024,

http://www.mjmmusic.pl/historia,aw13,14

[37] IFPI Music. Piracy Report 2000, 2000, IFPI, 2000, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024,

https://web.archive.org/web/20081117004101/http:/www.ifpi.org/content/library/Piracy2000.pdf

[38] The recording industry commerecial piracy report 2003, 2003, IFPI, 2003, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024 https://web.archive.org/web/20081117004029/https:/www.ifpi.org/content/library/Piracy2003.pdf

[39] The recording industry commerecial piracy report 2004, 2004, IFPI, 2004, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024 https://web.archive.org/web/20101126153042/http://ifpi.org/content/library/piracy2004.pdf

[40] IFPI Music. Piracy Report 2000, 2000, IFPI, 2000, [online] retrieved 14 April 2024 https://web.archive.org/web/20081117004101/http:/www.ifpi.org/content/library/Piracy2000.pdf